The Value of Process Curiosity

- nickplaters

- Apr 8

- 9 min read

If it happened once, then it probably happened many times…

Organisations today are filled with people solving what they treat as “one-off problems”. If you sit with a complaints team, they spend most of the day fixing each customer’s problem one by one. Meanwhile, over in the contact centre each agent will be trying to “resolve” every call or chat they receive, one problem at a time. Ironically, organisations have learnt that the more they can give their staff simple, but repeatable problems, the better they will be at resolving them. Often the front-line staff recognise that these aren’t one-offs at all, but recurring issues. They still just act on the issues one by one. Everyone has been conditioned into being good at solving these instances of issues, so they don’t ask, “but why is this happening again and again?” Somehow “process curiosity” has been conditioned out of the culture of many organisations.

The volume of issues and problems is such that many organisations are having to work hard to have enough people trained and available to solve all these “repeated one-off” problems. Process curious people and businesses dig a little deeper and ask why this activity happens. That is rare as most businesses are stuck on a giant hamster wheel with management and front-line staff running hard to stay on top of all these instances. It is often the case that those working in this system don’t have the time or role to question why this activity happens. There is either no time or no interest in “process curiosity”.

What is Process Curiosity?

Process curiosity is like an annoying three-year-old child asking “why?” all the time. Process curiosity is about asking questions like:

- why did that happen?

- is this a one off or a recurring issue?

- how many other customers did that impact?”

and most importantly

- how can we fix this and stop it happening again?

There are rare organisations who have made process curiosity part of their DNA. For example, Jeff Bezos at Amazon famously sends emails to management with a subject line of “?”. This could be a question about why an item was late or why a damaged good was received by a customer. Recipients of these emails have a limited time to respond with their explanation of how the problem will get fixed, not just for that instance, but all possible instances of the same problem. These emails demonstrate process curiosity at a corporate level and drives systematic improvement.

Most of the organisations we have worked with have at best, a few people who work and think in this process curious way. Ironically, they have far more people working “in the problems” than “on the problems”. At one point a major Telco had over 500 people in their complaints team, but few of them were dedicated to investigating and fixing the underlying causes of the complaints. In this paper we’ll examine the value of thinking this way, a few of the techniques that can be applied and then assess why it is becoming a lost art and the barriers that prevent it.

The Value of Process Curiosity

Process curious organisations recognise that eliminating the root cause of issues not only saves money but also reduces the effort of the customer and increases their loyalty. A major water utility used to see complaints as a “lens” onto more significant areas of improvement. Process issues tend to cut across the whole pyramid of contact. A single process issue causes complaints and escalations at the pinnacle, repeat contacts in the layer below and then a broader base of initial contact (see picture). Each issue can be thought of as a ”slice” through this costly pyramid. For example, a customer complaining that discounts have not been applied as agreed in the sales process has probably made contact when their first bill was wrong, again when it wasn’t fixed and finally to lodge a formal complaint. The complaints team may well fix this problem for this customer, however, may not take the time (or indeed have the remit) to analyse why discounts are not correctly applied for hundreds of customers each year.

Process curiosity can help address the costs across this contact pyramid but there can be other costs such as loss of revenue and departing customers. One major insurance business recently confessed a systemic issue to a regulator associated with discounts incorrectly applied leading to fines and court cases. The lack of process curiosity led to a multimillion dollar fine. A range of super funds have been fined for not asking or knowing how long their death claim processes were taking. Had there been earlier process curiosity perhaps the issue wouldn’t have impacted as many customers over an extended period?

Why is process curiosity scarce?

A combination of factors seems to prevent this way of working and we’ll cover budget and skill and separately look at the methods that work (the why, who and then the how).

Barrier 1 – Lack of budget and short-termism

In many organisations a short-term cost focus produces a limited investment in continuous improvement and deeper problem analysis. In one large consumer facing organisation there were eight hundred people taking calls and over ninety dedicated to complaints but only one person across that entire structure focused on continuous improvement. Another company closed a $1m improvement team, even though there appeared to be potential to cut $20m in failure demand from the business!

In contrast, in the early days of one retail start up, where front-line staff showed process curiosity and raised issues they thought could be fixed, some were rewarded with secondments to project teams to work on the issue. The organisation recognised that dedicating some short-term budget to long term fixes was worthwhile and that it was worth nurturing front line curiosity.

Barrier 2 - A complicit culture

The second ingredient for success is appropriately skilled people to follow through the issues and identify and design solutions. In organisations that have come to accept issues and problems as the norm, it can take a Challenger with a process curious mindset to question that norm. For example, in one operation a skilled designer was able to look at the end-to-end process and both fix potential errors and “leaks” that caused re-work. They recognised that inserting more work earlier in the process would eliminate a whole series of downstream activities. The result was a 40% reduction in workload. That external hire brought in a different perspective and was able to question everything.

Often the best combination of skills to solve these problems involves a deliberate mix of those who do the work now mixed with challengers external to the process to see the process in a new light. Challengers can question every aspect of a process and are given the “right” to be process curious. The external nature of Challengers means that they also find ways around the road blocks to change. It is harder for those “institutionalised” in a process to know what alternatives are possible and hence external Challengers can make a difference.

Barrier 3 – Speed over outcome

Unfortunately, some modern techniques for system and product development are adding to the “pile” of problems. Agile and “Minimal viable product (MVP)” delivery has become all the rage; and this can mean that problems and issues are built in as part of a minimal solution and then remain so. For example, one company rolled out an MVP product design with only limited IT support. The operations areas had to have extra teams dedicated to the workarounds and the issues that created. The organisation quickly scaled the product, and these workaround teams grew at the same rate. Scaling this product too soon embedded extra work and cost into the processes. This focus on speed and immediacy created the need for clean-up and redesign down the track but the expected clean up didn’t happen.

Barrier 4 – Measures create a narrow focus

Many of the areas that handle the symptoms of problems in organisations are measured purely on how they handle each instance or even the speed of response. Complaint teams, for example, are usually measured on their speed of response but are rarely measured on reducing the causes of complaints. They spend all day fixing problems and are rewarded for doing so. Other customer facing staff also get rewarded for “doing” not “questioning”. In one superannuation business, processors got “credits” for rejecting requests that lacked details. This produced lots of work around sending forms back and handling them a second time. Nothing in the measurement system got the processors to flag repeated problems and where customers got confused. Having it set up as an outsourced business unit, which separates those who control the process from those who do the work, added another built-in barrier to process curiosity.

Some quick techniques to create process curiosity

A range of techniques is typically needed to design effective solutions. One simple technique to understand the problems involves what we call “stapling yourself to an X”. This is a method to follow a process through an organisation. For example, the X could be a new order, a renewal or a claim. Following the X traces the reality of what happens and can happen for a customer. The goal here is to clarify how processes work, rather than how they were designed to work in theory. Part of the curiosity here is on what goes wrong and why and probes the issues and problems.

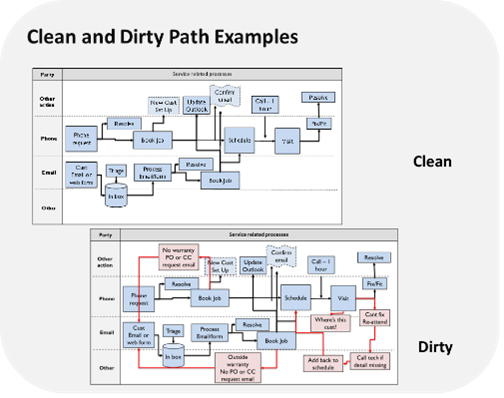

When we are conducting this technique, one very useful visual artefact is to draw “the clean and dirty path” of a process. The clean path represents what should happen and the dirty path shows what can and is very often going wrong. This simple comparison makes the inherent lags and faults, and therefore the opportunities, more visible. One of the reasons we suspect process mapping is used less in business today is that the process maps are typically written to illustrate the unrealistic perfection of a designed process. They represented this ‘special case” of how things were supposed to work rather than how things “really” work. This technique focuses more attention on how the processes work in reality and the problems it has created.

Today there are AI driven tools that can assist with this kind of process curiosity. They can track the actual execution of processes right across a business and report on the cost and complexities of processes in detail. They are capable of sizing and measuring the variations in processes and can track a whole range of dirty paths and combinations. Some businesses are setting up these tools to keep control of their processes and to show them the true costs of these issues.

Other useful techniques are methods to explore the root cause of an issue or problem. Techniques include “five-whys” analysis which probe causes at multiple levels and “fishbone” or Ishikawa analysis that also assesses causality. These techniques sound simple but take some discipline and skill to apply. Getting to the causes, is also only half the battle as some form of solution design is needed.

Another technique we find useful is to classify contacts and interactions based on how the business and customer perceive them. This helps separate the contacts and processes customers want to make from those that show problems. That technique creates four likely strategies as shown. The contacts that are irritating to both customer and organisation e.g. often processes that are delayed or wrong, become candidates for examination and elimination.

What can it be worth?

These techniques often illustrate the potential for improvement. At one organisation, classifying the contacts showed that over 70% of contacts had elimination potential because they were customers “chasing the process” when it took longer than they expected or confused by the process. The sheer volume of these contacts showed the potential pay back in investing more in the process that was in backlog. In another business, the volume of errors and rework that could be quantified as a result of manually entered forms, built the case for greater automation and digital forms for all key processes.

Isn’t finding the problem, the easy bit?

Finding the size of the problems that need fixing is of course only step one. Designing and implementing solutions is the next step. This is the next level of process curiosity by asking “what might be needed to change this?”. In this paper we can’t tell you what the answers are but some of the analysis techniques we have described will get you close. The root cause of a problem can trigger a range of solutions. For example, if “people” keep making mistakes the problem may be training, but it can also be poor form design, system design or checks within the process. We would recommend assessing solutions by considering all possible answers such as people, process, technology or measurement levers or any combination of those. This is where good solution architects earn their keep, and we need many more of them working in corporates today!

Summary

In this paper, we hope we have explained the value of being process curious. There are some amazing tools and tricks available and far more detail than we could include here. If you would like to discuss this further, please feel free to get in touch at info@limebridge.com.au or call 03 9499 3550 or 0438 652 396.

Komentar